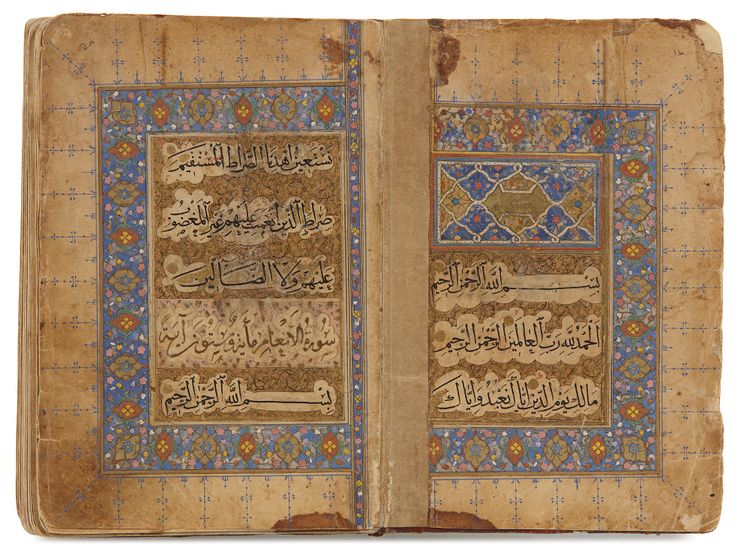

A QURAN SECTION ILKHANID, DATED 720 AH/1320 AD, ATTRIBUTED TO ABDULLAH AL-SERAFY IN 720 AH

An Arabic manuscript on paper, 104 leaves, 5 lines to the page, written in fine naskh script in black ink, 5 surahs and 381verses including surah Al Fatiha, surah Al An’am, Al Kahf, surah Saba and surah Fatir. Surah headings written in gold thuluth script within gold-ground floral panels. Al Tajwid, in diacritics in red ink. Opening illuminated double-page frontispiece elaborately decorated with interlacing polychrome flowers against a punched gold ground. The last double-page in five lines to the page written in naskh script, laid down on clouds against a gold ground, binding with gilt-stamped medallions and cornerpieces composed of scrolling vines. 18.3 by 12.5 cm.

CATALOGUE NOTE The calligrapher ‘Abdullah al-Serafy, who is known to have died after 1345/6 AD, was the son of Khwaja Mahmud Sarraf, and appears to have worked and lived in Tabriz his whole life. He trained under Sayyid Haydar Gandah-navis, one of the six famous pupils of Yaqut al-Mustasimi, the most celebrated calligrapher of the thirteenth century. In the tradition of Yaqut’s work, Al-Serafy studied the six scripts used by the calligraphers of the Iraq school, but also achieved great fame as a designer of architectural inscriptions. Indeed, it is likely that he was responsible for the calligraphy on two monuments in Tabriz, the Demasqiya Madrasa and another building that acquired the popular name ‘emarat-e ostad sagared (‘building of the master and the pupil’), commemorating the work of Al-Serafy and his pupil Hajji Muhammad Bandgir. ‘Abdullah al-Serafy’s calligraphy was held in such respect in the fifteenth century that his style was followed by the scribe Jafar Tabrizi, a tutor of ‘Abdullah Haravi and confidant of Prince Baysunghur, the well-known Timurid bibliophile. Furthermore, the Safavid calligrapher Dust Muhammad, active during the reign of Shah Tahmasp (r.1524-76), claimed that the naskh tradition of Khurasan calligraphy had its roots in the earlier work of Al-Serafy . Only a very small number of examples of Al-Serafy’s work have survived, including a Quran juz’ (30) dated 728 AH/1328 AD in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (MS 1468, published in A.J. Arberry, The Koran Illuminated, Dublin, 1967, p.41, no.136 & pl.49); a Quran in the library of the shrine of Imam Reza, Mashad, and a calligraphic page in the Iraq Museum, Baghdad. A Quran, copied by Abdullah al-Sayrafy and dated 744 AH/1343 AD, is in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Istanbul [Inv No.178], whilst another Quran copied by the scribe, dated 745 AH/1344 AD, is in the Topkapi Palace Museum Library [Inv No.EH 49]. Abdullah al-Serafy has been celebrated for his Risala fi ‘ilm al-Khatt on the canons of calligraphy. The earliest known copy of this work, transcribed by a later scribe, dated 877 AH/1472 AD, is now in the Manisa Library [Inv. No.6436/1], Turkey. His Qawaid Khatt-i Thulth, now in the Ridawi Library, Mashad, is also among his scientific works on calligraphy. Further examples of Al-Sayrafy’s work can be found in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection, London, including a Quran written in rayhan and thuluth scripts (Acc.No. QUR832, see D. James, The Master Scribes, London, 1992, p.112-13, no.25) and a calligraphic page from an album of muraqqa’at (Acc.No. CAL25, see N.F. Safwat, The Art of the Pen, London 1996, p.76, no.42).

The Chester Beatty Library Quran juz’ (also published in D. James, Qurans of the Mamluks, London, 1988, p.241, no.52) shares with the present manuscript an exceptionally fine and crisp Naskhi hand, and was also included by Pope in the Survey of Persian Art of 1938 (A.U. Pope [Ed.], A Survey of Persian Art, London & New York, 1938, vol.V, pl.939B). Such is the beauty and high quality execution of the naskh script employed by Al-Sayrafi in the present Quran, with its neatness of form and regularity of spacing, that it is strongly reminiscent of the hand of his predecessor Yaqut Al-Mustasimi himself. Indeed a clear comparison can be made with the script of the present Quran and one generally accepted by scholars to be the work of Yaqut in the Topkapi Saray Library, Istanbul (E.H.76, published in M.Lings, The Quranic Art of Calligraphy and Illumination, London, 1976, p.55 & nos.24-25), written in 669 AH/1270-1 AD; both manuscripts are remarkable for the extreme clarity of their naskhi script, a hand considered by many to be the most important among Quranic scripts. A final example of Al-Serafy’s work can be found in an album composed of calligraphic specimens of the ‘six scripts’, a project sponsored by the Timurid prince Baysunghur (1397–1433) and now kept in the Topkapi Palace Museum (H.2310). The album includes the work of seven master calligraphers: Yaqut Al-Mustasimi, Mubarakshah Ibn Qutb, Arghun Al-Kamili, Ahmad Ibn Al-Suhrawardi, Yahya Ibn Jamal Al-Sufi, Muhammad Ibn Haydar Al-Husayni and Abdullah Ibn Mahmud Al-Sayrafi. One single page of text in the album (in Tawqi script) signed by Al-Serafy is dated 714 AH/1314 AD (see D.J. Roxburgh, The Persian Album, 1400-1600, London, 2005, p.48, fig26, and pp.37-83 for a full discussion of the album).