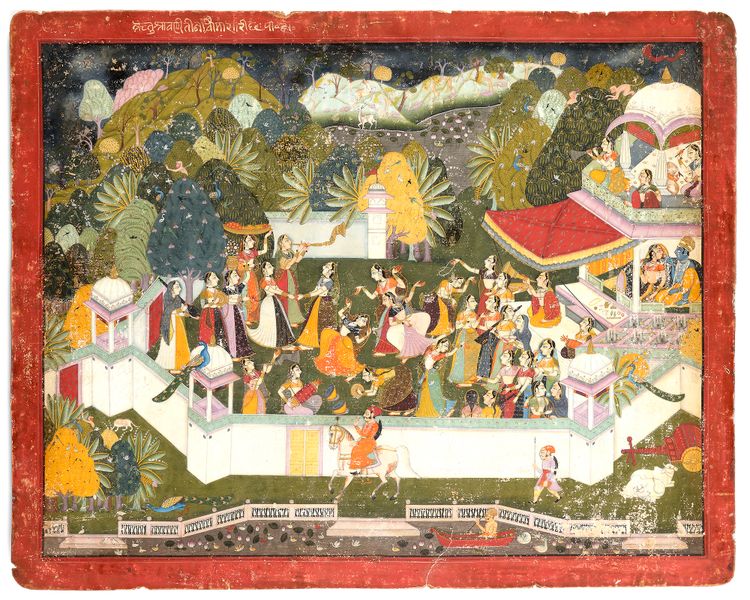

BARAHMASA (TWELVE MONTHS) ILLUSTRATION DEPICTING THE CHARACTER AND SYMBOLISM OF THE LATE SUMMER RAINY (SRAVANA & BHADON) BUNDI, RAJASTHAN, CIRCA 1780

Opaque water color on paper.

50.5 by 39 cm.

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Germany.

CATALOGUE NOTE

Lotus-filled lakes and streams coursing with rainwater were

ubiquitous aesthetic spaces in the pictorial and poetic imagi-

nares of early modern northern India. An eighteenth-

century painting, likely made in the town Bundi,near kotah.reveals the elements and emotions associated

with the monsoon Along with the standard tropes of besotted lovers, lightning streaks, thundering clouds, crying

peacocks, monkeys, and dears, the painter

invites us to savor the lotus-filled lakes created by the

onslaught of rain. Blue-hued Krishna and his lover sit together

in a courtly pavilion while a group of ladies celebrates the rainy

season with dance and song or enjoys its cool breezes, playing

on the swings in the verdant landscape. Because ascetic wan-

dering and travel were forbidden during these rainy months,

on the outside of the wall a nobleman astride a white

horse. The artist's goal was to convey the emotional, social,

atmospheric, and sensorial experience of the monsoon season.

On the painting's border, a scribe notes(Retu Sawani Teez Chaumasa ro Tuohaar).Meaning four months of the rainy season. That the picture

depicts the months of Savan (July and August) and Bhadon

August and September), covering the anticipated weather

cycle of the rains, starting from late summer leading up to the

Wetter days. The inscription identifies the painting's presenta-

tion of the bhava of the rainy months.

Poetic verses associated with the rainy months of Savan

and Bhadon were not always inscribed on monsoon paintings.

However, the citation of familiar images and tropes across

innumerable paintings persuades us that historical viewers,

like contemporary art historians, plausibly related these

painterly visions to the literary descriptions that circulated

within courtly contexts and beyond. The poetic genre of the

barah-masa was the paramount expression of the moods of

people, places, flora, and fauna in the rainy season. The barah-

masa is always structured as a lament divided into descrip-

tions of the twelve months, each expressing the pain of

separation when the lover of a nayika, the female heroine or

lover in the Sanskrit and Hindi courtly literary tradition, goes

abroad.' The poet Keshavdas, one of northern India's most

prominent exponents on aesthetic theory in Brajbhasha, com-

posed an extensive barah-masa in his acclaimed Kavipriya

(1601).° His verses describing the rainy months of Savan and

Bhadon are in the voice of a woman desperately trying to convince her lover to stay.

A painting from the series is in the Virginia Museum of fine arts, Richmond