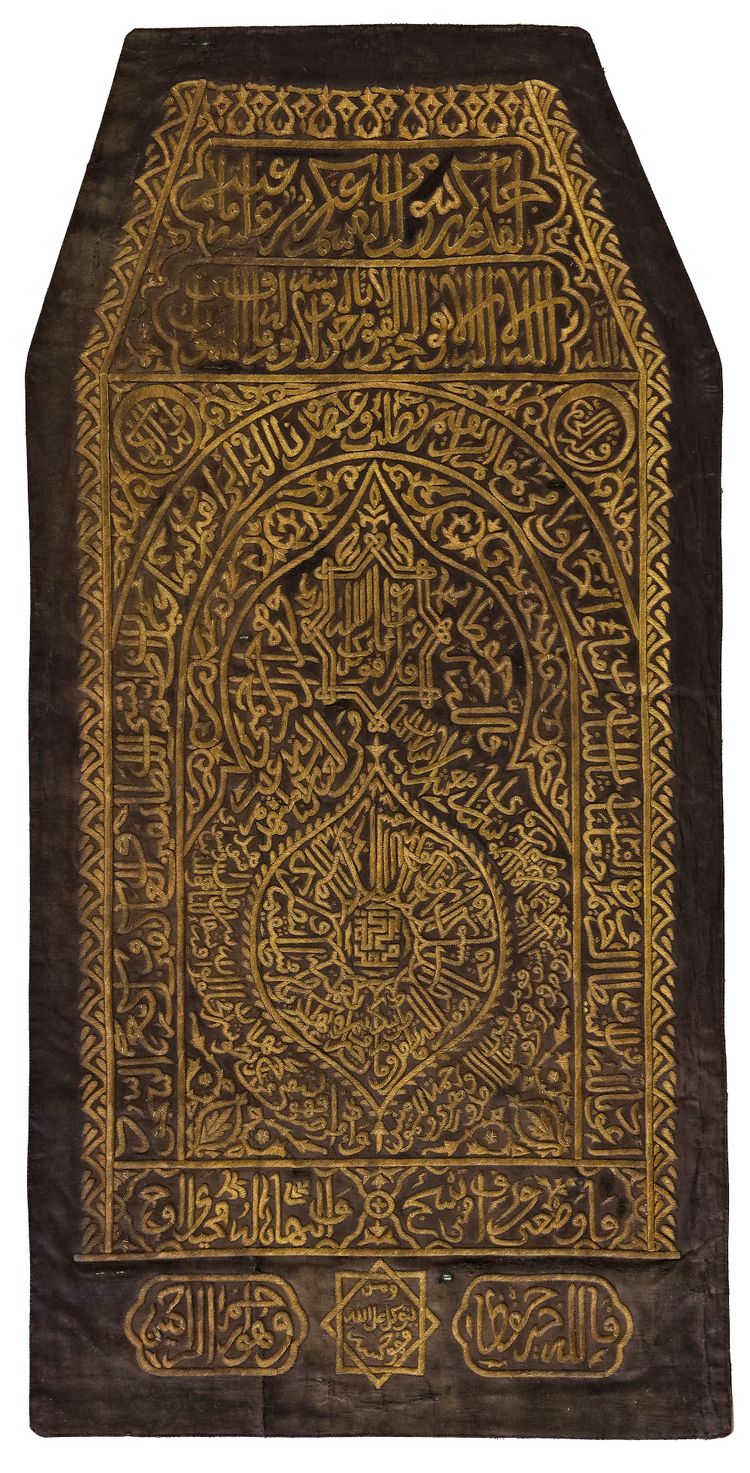

A LARGE METAL-THREAD WOVEN SHRINE COVER NORTH AFRICA, 17TH CENTURY

Formed as an arch, the central niche with pointed arch under semi-circular top, the spandrels with crescent shaped medallions filled with religious inscriptions in maghribi and kufic between floral scrolls.

230 by cm.

This impressive black silk and gilt metal thread woven panel was intended as a shrine cover on the model of the luxurious textiles (kiswa) woven for the Maqam Ibrahim in the Haram in Mecca. They are well documented and are composed of four panels of identical form with truncated top, as shown here. A 19th century Ottoman cover made in Cairo for the Maqam Ibrahim is in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection (Venetia Porter (ed.), Hajj, Journey to the heart of Islam, exhibition catalogue, London, 2012, fig.6, p. 30-31). As for the Maqam Ibrahim, our textile originally covered a shrine with truncated pyramidal top. In these examples, the finely drawn calligraphy is bordered by lush floral scrolls. However the decoration of our panel is clearly arranged as a monumental door or niche. This composition also appears on the cover of the tomb of Sulayman al-Jazuli, the saint and author of the renowned Dala’il al-Khayrat. The tomb, located in Marrakesh, is decorated with embroidered silks. The long sides are decorated with three successive arches encompassing an almond-shaped medallion filled with calligraphy; a very similar composition to that of our work (Yannick Lintz, Claire Deley and Bulle Tuil Leonetti, Le Maroc médieval, exhibition catalogue, Paris, 2014, fig.1, p.553). A modern photograph of the Tomb of Moulay Idriss in Moulay-Idriss Zerhoun shows similar covers in what was possibly the original location of our cover (https://histoireislamique.wordpress.com/2014/10/12/la-dynastie-alide-des-idrissides-789-985-passage-relatifs-par-ibn-khaldoun-al-hadrami/). It is very probable that our cover was woven to decorate the shrine of an important Moroccan historical figure such as Moulay Idris, the founder of the Idrisid dynasty in 789 AD.

There is a long tradition of weaving in Islamic Spain and North Africa. Almeria in Andalusia was famous during the Almoravid period as an important weaving center and it is during the 11th century that gold thread appears on weavings. The silk textiles were woven in Spain and subsequently in Morocco – possibly in workshops that moved to North Africa following the expulsion of the Jewish and Muslim communities during the Reconquista. Some of the largest textiles are military banners, two of which produced for the Marinid sultans Abu Sa’id ‘Uthman (dated 1312 AD and made in Fes) and Abu al-Hasan (dated 1339-40, also made in Fes). As in the present work, they are made of silk and metal thread and decorated with Qur’anic verses.

The calligraphic style of the Qur’anic inscriptions decorated our textile is typically Moroccan. The fleshy serpentine script derives from earlier Nasrid and Merinid calligraphy, later focusing on filling all space available to the scribe. It has obvious links to local manuscript illumination but is also under the distant influence of Ottoman art, as shown by a mid-16th century Ottoman silk tomb cover from the period of Sultan Sulayman (Y.H. Safadi, Islamic Calligraphy, London, 1978, cat.131). An 18th century tomb cover from Morocco now in the Quai Branly museum, offers a close comparable example for the use of various calligraphic devices in one single composition: geometric kufic squares are woven aside radiating thuluth compositions, bordered with crescent-shaped medallions (74.1961.5.1 ; Safadi, op.cit., cat.125, p.113). As in the Quai Branly example, our piece demonstrates an ambitious use of calligraphy: a true prowess of design as well a impressive technical achievement.