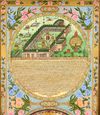

A QIBLA FINDER PANEL MADE IN THE STYLE OF PETROS BARONYAN, ALSO KNOWN AS AL-BARUN AL-MUKHTARI, CONSTANTINOPLE, 1178 AH/1765 AD

Constantinople, 1178 AH/1765 AD (dated above the frame)

Case overall 84.8 by 40.5 cm.

Qibla finder comprising a rectangular wooden panel with two printed roundels, the upper one with a depiction of the Haram al-Sharif in Mecca and a description by the inventor of the instrument, the lower roundel with a depiction of a map of the world signed in a cartouche by Abdulwahab Siddiki, thereunder a series of tables listing the cities and places of the world. The description mentions al-Bārūn al-Mukhtariʽ as the inventor and is dated 1151 AH/1738-9 AD.

This qibla finder map in a wooden frame, dated 1764/65 AD, is modeled after the original series of Qiblafinders, invented and made by Baronyan (Bārūn al-Mukhtariʽ) some 30 years earlier.

Baronyan, the original inventor of these instruments created this genre of qibla indicators for the Ottoman Grand Vizier, Yegen Mehmet Pasha in 1738/39 AD. These prints were first mounted in a circular box form and later in a wooden frame, as is the case in our object.

DATING

At the center of the upper part of the panel there is an Ottoman inscription, where the date is given as 1178 AH, which corresponds to 1764/65 AD which is the last year that Baronyan was in life. A very similar panel was sold in 2002 in Bonhams with the same date of 1178 AH given on top of the frame.

INSCRIPTION IN THE FRAME

"Māšā Allāh (God has willed it)!

ماشاء الله

I am such a treasure of a Qibla-numa

وهی پاك خزائن قبلة نمايم

I am the beginning of the thing/picture which decorates the world"

مبدأ هئيت جهان ارايم

In the year 1178 [1764/1765]

سنه ١١٧٨

MAKER

The map in the frame is signed by Abdulwahab Siddiki in a small cartouche left to the world map, who is futhe unknown to literature. While the same cartouche is left empty in most of the instruments made by Baronyan, some examples printed in manuscripts are signed “Mıgırdıç Galatavi”.

It seems like it that Baronyan cooperated with an Armenian copper engraver Mıgırdıç Galatavi, who is also known from the engravings he made for the maps of the work Cihannüma, published by the Ottoman printer Müteferrika.

Our model is completely drawn and painted by hand, probably by Abdulwahab Siddiki, as his name is given in the cartouche.

BACKGROUND

In Islam, the geographical directions towards Mecca, where “God’s House’, the Holy Kaaba is located, is of crucial importance. Orientation towards the “Qibla”, as this direction is called, is important not only for the daily prayers but also for burials. The problem of finding the Qibla, was a non-trivial problem and as the Islam spread over a vast geographical area, Islamic scholars realized that the basic thumb rules are not accurate enough and devised very sophisticated methods in mathematical astronomy and geography for solving this problem. Islamic scholars also invented so called “Qibla-finders”, portable devices which make it easy to look up the Qibla direction relatively easy, without having to refer to com- plex calculations or to handbooks.

From the 18th century onwards, a tradition of qibla indicators came into existence which are also very characteristic for their artistic decoration in the form of floral patterns or miniatures depicting Ottoman scenes. One such instrument, the Qibla-numā-yi āfaqi was invented and produced in 1151 AD/1738 AD by a certain Bārūn al-Mukhtari, identified with Petros Baronyan, the dragoman from Kayseri who worked for the Dutch ambassador Justin Colyer as a dragoman. [Günergün, 2017]

According to the information Baronyan gives in the inscription on the instrument, in 1146 AH/ 1733 AD, he presented Grand Vizier ‘Alī Pasha (1732 – 1735 AD) a treatise called Jam-numā fī fann al- Jughrafyā and was ordered to prepare a rubṭ-i shamsī (a sundial) under the name of rub-i mustadīr (a portable universal equatorial sundial with 2 rings). For this he obtained a liberal recompense and, encouraged by it, started work on a new invention: a Qibla indicator. The Ra’īs al-Kuttāb Mustafa Efendi enabled him to present his device to the new Grand Vizier Yeğen Muhammed Pasha ( 1737-1739 AD). [Minorsky, 1958]

The name of the maker, Petros Baronyan, knows some variants. In the inscription of the Qibla indica- tors his name is written as Bārun/ Bārūn al-Mukhtari (“Baron the Inventor”) while in his translations his name is written as “Pitrū Walad Bārūn al-Armanī=پترو ولد بارون الأرمني”. The German Orientalist Franz Taeschner calls him “Petro veled Baron” and the Turkish historian of Science Adnan Adıvar names him Bedros Baronian. [Günergün, 2017]

Petros Baronyan ( Baronian) was born at an unknown date in the Central Anatolian city of Kayseri. He entered the service of Count Jacobus Colyer (1657-1725), the Dutch ambassador in Istanbul, at an early age, and later became the dragoman of the legation of the United Provinces. After the death of Colyer in 1725, he acted as dragoman-in-chief ( ser-tercüman ) of the embassy of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in Istanbul. [Günergün, 2017]

USE OF THE INSTRUMENT

The inscriptions below the topographical image on the lid are in Ottoman Turkish and provide instructions on how the indicator can be used (including the signature of the maker and the date and place of production.) For the full functionality of the object, a pointer, fixed in Mecca and a compass are necessary.

Furthermore, it is interesting to read that this instrument was not only used for finding the direction of Qibla but was also intended as Mihrab as described in the explanation section under the geographical map:

mezkûr bir mahallin kıblesin bulub teveccüh esnâsında bu şerhi muhtevî pûşîde-i kıble-nümânın pîrâmında müteharrikdir çevirüb kıbleye mukâbil edüb şerhin balâsında Kaʻbe-i şerîfenin şekli musavver mihrâb mesâbesinde olub.

Translation: If one finds the Qiblah in a certain place with this instrument than you can turn the device immediately in the open state towards the qibla after determining the qibla and to use the image of the Kaaba as a mihrab.

So it can be imagined that this instrument were taken with the Hajj Karavan and used for finding the direction of Mecca and after that used as an Mihrab where the audience behind could make his prayer together. This could be the reason why there is so few left of these panels.

SURVIVING INSTRUMENTS

There are only 4 other surviving of this panel type Qiblanuma’s.

1. I. Museo Correr, Venedig (Signature: M. 34394-34755)

Frame with cabinet, copper engraver cartouche gilded-empty, large cartouche gilded-empty, compass, gilded pointer

2. Sadberk Hanım Müzesi, Istanbul

(Signature: SHM 16074-Y.241) Frame without cabinet, copper engraver cartouche gilded-empty, large cartouche gilded-empty, compass, no pointer, but screw remains in Mecca

3. J. Alif Art Gallery, Istanbul 25.05.2006: Ottoman and Mixed Art Works – Lot 175

(privately owned) Frame with cabinet, copper engraver cartouche gilded-empty, large cartouche gilded-empty, compass

4. K. Bonhams, London 24.04.2002: Islamic and Indian Works of Art – Lot 380

(privately owned)

Frame with cabinet, copper engraver cartouche gilded-text large cartouche gilded-text handwritten, no compass but damage to the object from its removal

5. Our instrument. Drawn and painted by hand (see pictures and description above)

LITERATURE

Feza Çakmut, Surre-i Hümayün, Istanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Yayınları, Istanbul, 2008. p.126

Feza Günergun, “La traduction de l’Abrégé de la sphère de Jacques Robbe, géographe du Roi de France par Petros Baronian, drogman à Istanbul : Cem-nümâ fi fenn el-coğrafya”, La Révolution française [Online]. , 12 | 2017, Online since 15 September 2017

Venetia Porter, Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam, British Museum Press, London, 2012. p. 66-67

V. Minorsky. A Catalogue of the Turkish Manuscripts and Miniatures. Hodges & Figgis Co. Ltd., Dublin, 1958, p. 78 (no. 443)

Seracettin Şahin, Türk İslam Eserleri Müzesi: Emevilerden Osmanlılara 13 Asırlık İhtişam, Kaynak Publications, Istanbul, 2009. s. 264-265

Dilek Tezcan, 17. Ve 18. Yüzyılda Osmanlı Devleti’nde dekoratif süslemelerin bazı dini eserlere yansıması. Msc. Thesis, Gazi University,Ankara, May, 2015. p. 157-159

Thoralf Hanstein, A new print by Müteferrika (?) - A comparative view of Baron’s Qibla Finder. Bonner islamwissenschaftliche Hefte no. 46 , EB-Verlag, Berlin, 2021.